By: Claire Hadley

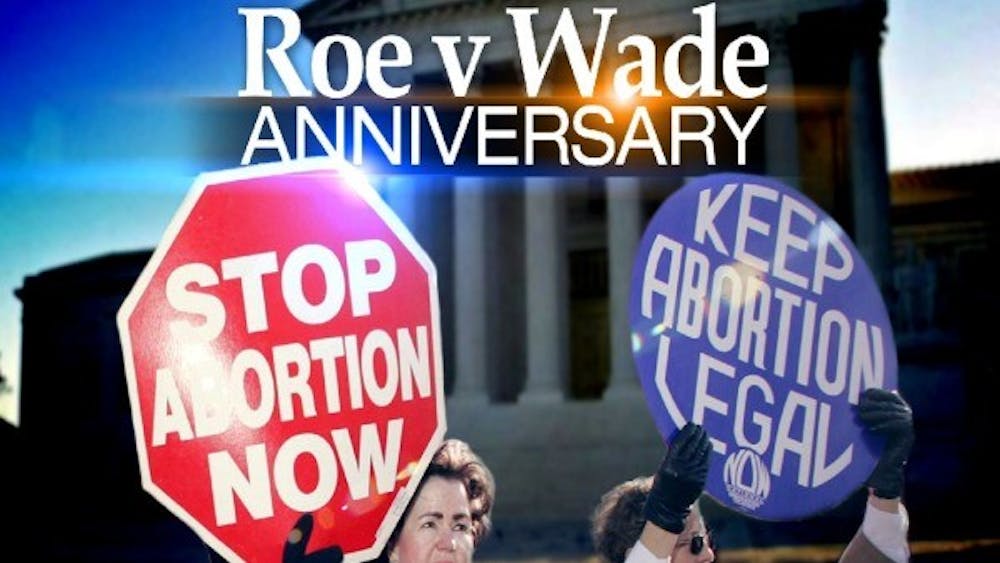

This month marks the 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, the court decision that forever changed America's approach to abortion. The following article is the first in a two-part series that will cover both the history of Roe v. Wade and the current impact of abortion and the pro-life movement throughout America today.

Norma McCorvey is Jane Roe, a woman who has never had an abortion. Most people at least recognize the name Jane Roe from the landmark court decision Roe v. Wade, but few people know what really happened and why abortion is still a national issue today.

Roe v. Wade, which had its 40th birthday this past month, is the event that labeled Norma McCorvey as Jane Roe, the woman blamed for the legalization of abortion.

But she was actually just a pawn, just the signature that allowed the feminist movement to win one more battle.

In 1969, Norma McCorvey was approached by Sarah Weddington, a lawyer who was hoping to lead the case to legalize abortion. McCorvey was pregnant for the third time, and she was hoping that Weddington would tell her where she could get an illegal abortion, knowing that Weddington had received one three years before. But Weddington always avoided the question, needing to keep McCorvey pregnant in order for the case to stay in courts.

Weddington needed a plaintiff for her case, and McCorvey fit the bill. So McCorvey took the pseudonym Jane Roe, signed the papers and was not heard from again.

"I was chosen because they needed someone to sign the paper and fade into the background, never coming out and always keeping silent," McCorvey said in her book "Won by Love." "If Sarah Weddington was so interested in abortion, why didn't she tell me where she got hers? Because I was of no use to her unless I was pregnant," McCorvey said. They met twice, McCorvey signed as the plaintiff and Weddington promised to keep in touch.

"Sarah had told me she would be there for me after my baby was born, but she never was-at least not after she got my signature," McCorvey said.

In her book, McCorvey quotes Debbie Nathan, a pro-abortion writer from the Sept. 25,1995, edition of the Texas Observer.

"By not effectively informing (Norma) of (where she could get an abortion), the feminists who put together Roe v. Wade turned McCorvey into Choice's sacrificial lamb-a necessary one, perhaps, but a sacrifice even so."

For three years, McCorvey went on with her life, having her child, working as much as she could and struggling with severe bouts of depression. During this time, she heard nothing from Weddington. One day she came home from work and picked up the evening paper. In a corner, she noticed an article announcing the Supreme Court decision of the Roe v. Wade case. "It was me! I had won!" she thought, but later she reconsidered.

"I had already delivered my baby and placed her up for adoption, so it really wasn't relevant to me," McCorvey said in her book.

She was confused and had many questions, such as why she wasn't at the Supreme Court when the case was being argued on her behalf. No one had called and updated her on the progress of the case or even told her that they had won.

"Sarah had all the time in the world for me before I signed up as her plaintiff; but once she had my signature, I was a blue-collar, rough-talking embarrassment. Sarah has passed herself off as my friend, in reality she used me," McCorvey later recalled.

McCorvey began to work her way into the pro-choice movement, something she actually knew little about.

"Ironically enough, Jane Roe may have known less about abortion than almost everyone else," McCorvey noted in her book.

She eventually began working as a receptionist at A Choice for Women, an abortion clinic in Dallas. While working there she began to be shocked by what she saw walk through the front door. Some of the girls were coming in for their fifth or sixth abortions. Some women were six months pregnant. Eventually, Norma began to question the morality of doing an abortion that far into a pregnancy. The reaction she received was less than understanding.

"What's your problem? This is an abortion clinic. Abortions are what we do," McCorvey remembered hearing in her book. She felt betrayed and used. "But Sarah Weddington...had never told me that what I was signing would allow women to use abortions as a form of birth control. We talked about truly desperate and needy women, not women already wearing maternity clothes," McCorvey said.

While McCorvey was working at A Choice for Women, Operation Save America (OSA), one of the leading frontline pro-life organization, moved in next door to the facility. Flip Benham, director of OSA, began reaching out to Norma and the other workers at the clinic, inviting them over for pizza and chatting with them on smoke breaks.

At first, McCorvey was very suspicious and hesitant, calling Flip Benham "Flip Venom." The only experience she had had with pro-lifers was stories on TV of the occasional violent attacks by radical pro-lifers. She was confused by how gentle and non-violent they were. "There has never been a single instance of a member of Operation Rescue who used violence during a protest," she noted in her book.

McCorvey eventually developed a friendship with the eight-year-old daughter of the Assistant Director of OSA, Rhonda Mackey. One day, McCorvey realized that she had to reconsider what she thought about abortion, because she would never want someone so sweet to not have a chance to live.

McCorvey ended up giving her life to Christ. She was baptized by Flip Benham, toured with OSA for two years and eventually started her own ministry, Roe No More.

When the court decided Roe v. Wade, it passed down what has become known as the trimester structure. During the first trimester of pregnancy, a state may not regulate abortion at all. While in the second trimester, a state may regulate abortion if it deals with the health of the woman. Once in the third trimester, a state may regulate or prohibit abortion to promote its interest in the potential life of the fetus, except when the woman's life or health is at risk, according to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

The court later rejected the trimester structure, instead affirming the central idea of the decision that a person has a right to an abortion until the point of viability. This is the point when a fetus may survive outside the womb.

But Roe v. Wade is not a law. It is a precedent law.

"Precedent means that the principle announced by a higher court must be followed in later cases," according to UsLegal.com.

So Roe v. Wade became a standard for all questions concerning abortion at that time, even though the decision was only meant for those involved in the case. But it became the standard, and since that day in 1973, more than 50 million abortions have been completed, according to the National Right to Life Organization.

To be continued on 2-15-13