By Ellen Hershberger | Contributor

A teenage girl waits for the results of a pregnancy test. Time stops as a little green plus sign appears on the stick.

What now?

She tells her parents, her friends, her boyfriend. They end the relationship but argue if one of them should keep the baby. Eventually they decide that putting it up for adoption would be the best course.

Mike Severe, associate professor of Christian ministries, and his wife Leeann felt God's call to help vulnerable children; they wanted to adopt.

After being approved as foster parents in 2006, they were chosen by the teen mom to parent her baby girl. They named her Hope. After seven months of living with the Severes in foster care, Hope became an official part of the family.

"After we adopted our first daughter," Mike Severe said, "we started doing foster care, not just to adopt, but just for kids who were most likely going to be reunited with their families, which is the main goal of all foster care: to get them back into a safe home, (a) family environment."

The Severes have fostered eight kids since Hope's adoption and are in the process of adopting three more. This is a rare success story; few foster children eligible for adoption find foster parents willing to adopt.

According to The Children's Bureau, an estimated 671,000 children were in foster care in the U.S. throughout 2015. About 25 percent of those children had the goal of adoption, but only 4 percent went to pre-adoptive homes (foster parents who are willing to adopt). The other one hundred and twelve thousand children were still waiting to be adopted.

"The reason more children are not being placed in pre-adoptive homes is availability. Not enough people are wanting to be adoptive parents," said James Wide, Deputy Director of the Indiana Department of Child Services (ICDS).

He explained further that these statistics could also result from some adoptive parents not initially classifying their homes as "pre-adoptive," then deciding to adopt later.

The Children's Bureau reports that the other 75 percent of foster children who are not up for adoption usually stay in foster care for less than a year. Over half of them will reunite with their families. Because of this, Wide said agencies need more "emergency homes," foster homes willing to host children for brief periods of time, despite how disruptive it may seem.

For the Severes, watching the children's transformation during those first few months of staying in their home is one of the rewarding aspects of fostering.

"We've seen children who couldn't do their ABCs in first grade, and in a month or two be reading at a second grade level," Mike Severe said. "They are just ready for it. And the environment did not allow that to happen. They just didn't have the care or safety necessary to learn in those situations."

But while changes in education, health and social skills might occur in mere months, deeper mental issues may challenge foster children for years. One in four foster children grow up with some form of PTSD that they deal with for the rest of their lives, according to Foster Focus magazine. Anxiety, depression and other mental disabilities can lead to isolation, lack of trust or anger issues. These issues can arise from abuse, neglect or other negative situations in their past.

Foster parents often see the effects of these incidents.

"It's very difficult to help kids work through those issues," Mike Severe said. "And how they've learned to cope as children is often very harmful to themselves or even destructive to the people around them."

To help foster children's behavioral health, Wide said the DCS licenses foster agencies and homes in Indiana to provide services such as therapy and counseling. Therapists address anything from homework skills to communication to attachment disorder. Some of the Severes' foster children have had up to seven hours of weekly therapy.

Out of the four to five states they have fostered in, the Severes have felt the most personally resourced by the Indiana State Department of Children and Family Services (IDCFS).

"The IDCFS I think is the most healthy and progressive that I've currently worked with," Mike Severe said. "I've never seen the children so well resourced with medical, emotional and behavioral help."

A major problem that the Severes have come across, however, is turnover in case workers. They have worked with 18 case workers in the last two years. According to Mike Severe, case workers serve in the position for a couple months, then get promoted, transfer or quit.

"It's just difficult work on (the case workers), because they are constantly working with some of the most difficult situations in our society and also probably not paid extremely well for that work," Mike Severe said.

Wide revealed that family case managers (FCMs) make a yearly salary of about $35,776. In 2016, the ICDS had a FCM turnover rate of 25 percent.

"It's no secret the FCM position is very demanding," Wide said, "and we lose FCMs for various reasons such as an improving job market, the pressures of the job and work related stress."

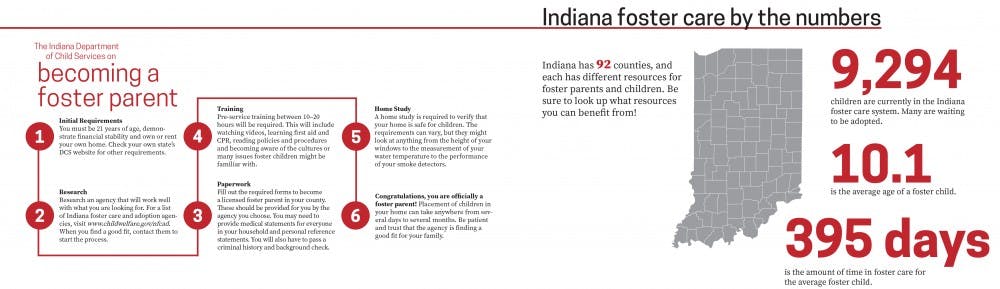

With all the challenges that come with fostering, potential foster parents need to be well-trained. Most foster agencies require between 10 and 20 hours of watching videos, reading policies and learning first aid and CPR.

Foster parents need support from the people around them, especially during the initial child placement process. The Severes' friends and family often bring meals or mow their lawn to assist them. "It's pretty chaotic for the first couple weeks when a new child is placed in our home," Mike Severe said. "And that's saved us, quite literally; those acts of kindness. There's ways for almost everyone to be part of the process of caring for the most vulnerable children in our society."